Terra incognita

...in cartography, regions not mapped or documented

We have to reject the worshiping of the new gadgets which are our creation as if they were our masters—Norbert Weiner

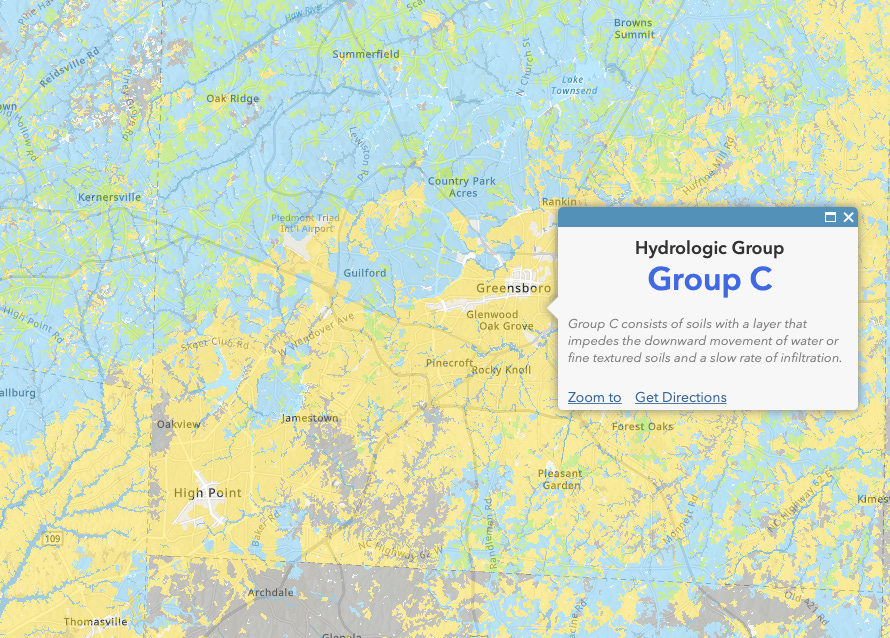

I am preparing a talk. Not just any talk. When I do deep dives into frameworks they often persist in whatever I do for a period of time. Take urban heat islands. The map shows these spots of intense heat concentration. The Environment Protection Agency defines them as:

“…urbanized areas that experience higher temperatures than outlying areas. Structures such as buildings, roads, and other infrastructure absorb and re-emit the sun’s heat more than natural landscapes such as forests and water bodies. Urban areas, where these structures are highly concentrated and greenery is limited, become “islands” of higher temperatures relative to outlying areas. Daytime temperatures in urban areas are about 1–7°F higher than temperatures in outlying areas and nighttime temperatures are about 2-5°F higher.”

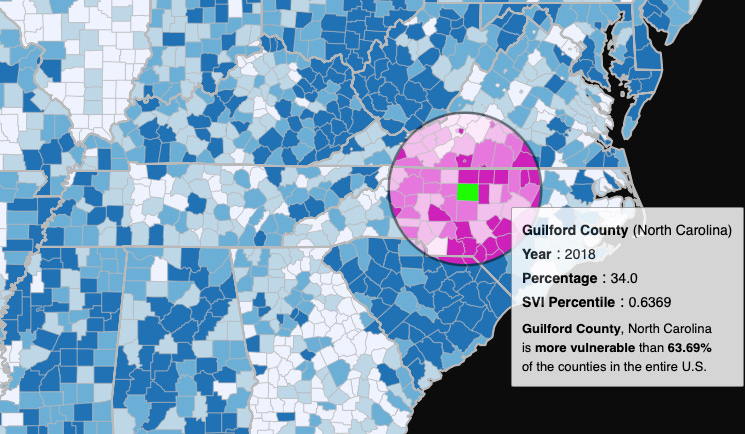

The first part of the stories I tell is location. Where are the heat islands and how do they impact the surrounding areas and the people that live there? Yes, certain segments of the population have been coerced and even forced into living in these areas of low economic investments as recent as the 1930s. These were predominately brown people that were denied ascension to wealth that many of us take for granted as home owners. But we seem to forget that many of these neighborhoods have locked-in land use ordinances meaning that the impervious ground, increased temperatures, lack of vegetative growth, proximity to highways and commercial industry not to mention lack of adequate transportation or nutritious foods are self perpetuating but not beyond the grasp of smart and compassionate policy.

Health systems have a certain reach as do medical facilities, physician groups, and certainly community health care providers are focused on specific demographics. You might be surprised how often the “where” of a problem is neglected or not under consideration. My colleagues show the slides of increasing rates of this or that—or how one population described as “underserved” is experiencing an uptick in disease.

The solution is not about victimizing the residents of underserved areas but about making the right investments into these communities. If you understand the risk it should reorient your strategy to improve the outcomes.

You know how you identify a car that you might be considering purchasing? All of a sudden wherever you go you notice this particular vehicle. I experienced this with the work of Daniel Schmachtenberger. His fundamental work focuses on existential risks posed at the hands of humanity. For example, man-made climate change, and ‘exponentially growing technologies like AI, biotechnology, and nanotechnology’.

We have a way—in general—of externalizing harms in the name of doing good. Daniel describes them as generator functions of existential risk:

Rivalrous dynamics: if we don’t fish the dwindling ocean populations someone else will—so we might as well do it too. He also cites the arms race as an example. Each agent attempts to run exponential externalities on a finite planet. The global dynamics in the collective are self-defeating but in the short term we envision dominance.

Subsuming of substrate: Our civilization requires the substrate but we continue to degrade the resources in the name of power and attention fueled by rivalrous dynamics. Think about the clamorous pursuit of elevating GDP—at all costs.

Exponential technology: Think about this as the power of the printing press being subsumed by the exponential power of social media. The micro-targeting of technology to reach billions of people in a matter of seconds.

It is impossible for me to talk about data analysis in healthcare without first explaining generator functions and how the decisions we make drive the outcomes we are attempting to improve. We use terms like adherence to medical treatments to passively blame the patient when their health outcomes stagnate or fail to reach stated goals.

In the name of health if we continue to ignore the impacts of man-made climate change in our communities, the legacy of locked land-use systems from the 1930s redlining or the systemic drivers of poor health nothing else will matter.

There are capitalistic drivers to create new restaurants while ignoring the impact on overall population health. Increasing the rate of impervious surfaces in our communities as our downtowns thrive impacts flooding, urban heat islands and a myriad of downstream effects. Pharmaceutical companies innovate to mitigate the cost of living in our capitalistic society and impart the costs at the point of care. Not enough of us ask how we are contributing to the endless cycle of pathologic senescence because to do so might mean we have to relinquish a benefit to the system we are creating.

We can see the vast threads of different stories that underly the data we publish and report when we visualize our data. If we can continue to hover around the surface and only tell part of the story—aggregated data for example—we will lack the insights needed to direct attention to potential solutions.

Technology gives us the ability to exponentially receive signals but it is only by understanding the risks and benefits will we be able to filter through the noise.

When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe—John Muir