Secret ingredients of a robust medical education strategy

Headlines within Continuing Medical Education broadcast record attendance at events, “Innovative” learning strategies, and tactics that lead us to believe we are making significant inroads in closing the gaps between evidence-based medicine and actual physician behavior at the point of care.

All those successes include big data integration and improved data literacy, or do they?

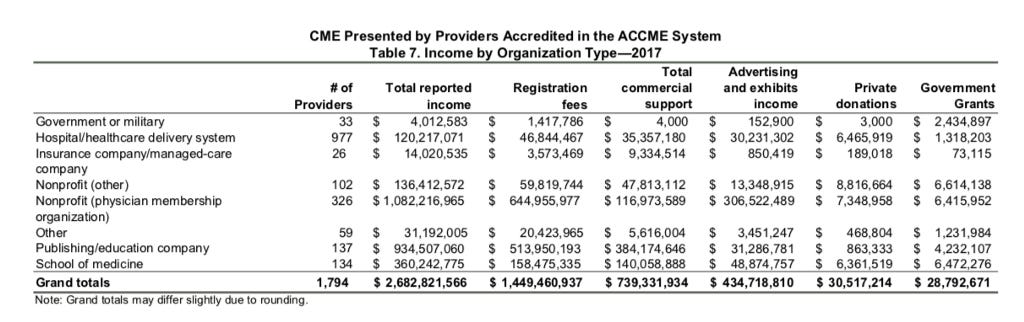

First, a little context. The CME industry includes close to $3 billion dollars in educational investments from a wide variety of financial categories including registration fees, commercial support, advertising and exhibits income, private donations, and government grants.

The ACCME’s Accreditation Criteria require providers to produce educational activities that are designed to change competence, performance, or patient outcomes. Providers are then required to analyze the changes that were achieved as a result of the activities.

Figure 4 (below) illustrates the percentage of CME provided in 2017 that was designed and/or analyzed for changes in competence, performance, and/or patient outcomes. — 2017 ACCME Data Report

Here is where the rigor starts to unravel. The measurement of competence and performance is inherently subjective or observational and simultaneously not evaluated utilizing sophisticated analyses. And the teeny tiny attention to actual patient outcomes is alarming.

Likert metrics, poorly constructed surveys utilizing outdated research methodology, and narrow focus to measure the activity instead of the actual physician level engagement or impact on patient outcomes appears to go unnoticed.

The Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) President and CEO writes in the annual report:

CME has responded to the changing health environment. Healthcare is practiced in teams — and clinicians need to learn how to work effectively as teams for the benefit of their patients. While CME traditionally has been focused on physicians, it has never excluded other professions. This data report shows that the number of interactions with learners other than physicians, such as nurses, pharmacists, and physician assistants, has increased nearly 90% over the past 10 years. Overall, learner interactions (physicians and other learners) grew 57% during that time.

Why does this growth matter? Degree and training programs are the foundation of clinician education; for the rest of their careers, clinicians rely on accredited continuing education to help them provide high-quality, safe, compassionate, and effective care to the patients they serve. Those activities help clinicians absorb and process rapidly changing medical information and practice an ever-diversifying set of complex skills. — Graham McMahon, MD, MMSc Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME)

Not to be all sturm and drang but I disagree regarding the claim that CME has responded to the changing health environment. I spend a lot of time in Washington DC and rarely see CME colleagues participating in discussions around value-based reform at the FDA, Brookings Institute, PCORI, Kaiser Family Foundation, or National Press Club.

Following a presentation at the annual Alliance for Continuing Education in the Health Professions, Systems Thinker Approach: Finding, Analyzing, and Gathering Data Insights for Modern Continuing Medical Education, I was asked to write an article for their open access publication, Almanac. I decided to pull the draft when I was challenged to provide citations from publications to support the findings and assertions regarding the importance and relevance of System’s Thinking in medical education. The whole point was the novel application of this approach to a complex problem.

How can innovation occur if we continue to simply rinse and repeat what we have been doing for decades? Why are so few willing to be first — seed a hypothesis and proceed from there?

A recent small survey of ~100 writers of CME needs assessments should stimulate a larger query of hypothesis test pathways to improve how we engage and evaluate learning in continuing medical education.

What it revealed — at least to me — is a potential skill desert unable to provide relevance and insight in our healthcare big data ecosystem.I have offered over the last few years to help improve the research methodology but my offer never received a response. I also reach out to colleagues with insights revealed from global travel and experience with comparative health systems — also crickets.

Respondents of the annual survey were primarily staff employees 56% (n=60) followed by freelancers 33% (n=35). I hope next year they will ask about roles within the company and link it to educational levels or areas of study. My concern is low data literacy among members of CME teams responsible for writing NAs or proposals seeking funds.

It would be a more rigorous study if unique identifiers of respondents allowed a stratification of data yielding a “tidy” data analyses — “Tidy data sets are arranged such that each variable is a column and each observation (or case) is a row” — wikipedia

It appears writer’s of needs assessments defer to the client or employer to designate what to include in a “first-rate” assessment. Lacking a definition of “first-rate” is also problematic. We might be comparing apples to tennis balls here.The top 3 highest ranked choices for what should be routinely included in needs assessments as measured in survey:

medical literature review 65% (n=70) — all publications are not created equal, how is data quality measured?

learning outcomes data 45% (n=48) — need more specifics here to be able to aggregate with confidence

clinical practice guidelines 42% (n=45) — funding source of guideline? Date of guideline?

This data should have been ranked — as it tells nothing about actual behavior when aggregated. If it was ranked, we could then assign probabilities.

Writers are also asked about tables, charts, or graphics — what to include in a “typical” needs assessment. Top 3 responses: (these also should have been ranked not “select all that apply” for valuable insights).

Alignment of practice gaps with learning objectives and desired outcomes 65% (n=68)

Results of clinician survey related to practice gaps 43% (n=45)

pre test/post test data from previous activities (with to without p values) 41% (n=43)

Coming in last (behind “I don’t include tables, charts, or graphics”, 17% (n=18) we find “Statistics showing effect size(s) from previous learning activities”, 12% (n=12). Not including the effect size? “No bueno”.

The problem here is that charts (my collective term for visualizations) are actually little arguments. They need to be read and interpreted and if necessary, challenged — not just slapped into a document. I think I noticed a Likert scale in the bunch but without ranking we know very little. For example, the response of 5 for one question is not comparable to a response of 5 in a different question.

I do applaud the authors of the survey (both work in CME) for efforts to measure the practice environment but I believe we left a lot of data on the table. You can read more here for thoughts on improving our approaches to CME.

I have worked in CME for at least 15 years or so. I consider myself a recovering CME professional. I had to step out of the bubble to notice the limits of our specialized and industry specific practices. Work in health economics, health policy, and biostatistics highlights the limited scope of “analyses” integrated in design, development, implementation, and evaluation in CME. If anything, the role of CME is even more critical as medical education frameworks evolve to address the shifting healthcare landscape.

Providers are expected to negotiate health policy, health economics, and the rigor of clinical research in decisions made at the point of care. The patient is now a stakeholder and must be informed regarding risk/benefits of treatment options and impact of care on quality of life. Community resources are also engaged in many consultations to aid in improving patient outcomes challenged by social determinants of health. That’s a lot of heavy lifting for a poorly constructed multiple choice question.

As fee-for-service is replaced by value-based healthcare the traditional educational structures must evolve along with the architecture of outcomes and assessment. Most importantly, we need to define “value” based on each stakeholder.

There are trade-offs especially in the evolving age of patient-centered care. Insights gleaned from population health are informative but critical thinking at the point of care requires the ability to synthesize multiple scenarios and outcomes both clinical and economic, risk benefits and cognitive biases and heuristics. Our challenge is to embrace the integrative thinking that allows us to considerassumptions, current reality, and critically assessed practices all together.

Too often we focus on one element or we defend assumptions as truth in stark either–or terms. We often set up false dichotomies when the most meaningful solutions lay between polar positions. I am talking to you writer of multiple choice questions to evaluate provider competencies and practice behavior.

The increasing complexity of practice necessitates the development, refinement, and application of additional and better assessment methods. These opportunities must include an emphasis on competencies beyond medical knowledge and basic clinical skills, such as systems thinking, quality improvement, interprofessional teamwork, and patient safety, while concomitantly attending to identity formation, wellness, and resilience.

In the modern age of big data we have access to control groups generated from American Community Survey Census Data, real gaps in care reported within the National Practitioner Data Bank, and limitless sources of data pointing toward patient outcomes such as MEDdra and FDA databases. Why are we still recycling outdated insights or industry funded guidelines as primary sources of information to guide care and improve outcomes at the point of care?

One way to measure treatment benefits and patient preferences for treatment is through the use of a stated preference discrete choice experiment (DCE) survey.

These surveys are designed to understand the strength of preference for the different constituents or attributes of a treatment intervention or care service. The choice experiment methodology is a powerful means of capturing patient, caregiver or physician strength of preference for the attributes of a treatment and makes it possible to understand the relative importance of attributes with respect to the degree to which people are willing to trade between them.

If you have questions I can be reached here…or on twitter @datamongerbonny

Originally published at www.dataanddonuts.org.