“one glorious, shimmering, and singular species”

Back in the days of too many conference invitations to accept I would often walk the conference hotel entering into unstructured but important conversations with policy makers, distinguished keynotes and leaders in their field and I always had a similar feeling. The people that need to hear this are not in our audience.

Health insurance executives were not talking to the healthcare provider making decisions at the point of care, policy makers used terms like “we” and “us” to a room full of “them”, and often large parts of the discussion were muted. Without complete outreach to solve seemingly intractable problems we are either grasping at low hanging fruit, preaching to the choir, or intentionally poking out our own eye.

It was moments like these that moved me to work in healthcare data literacy and to start this blog over 5 or 6 years ago. Yes, from time to time you might have to use a new tool to be able to access large datasets but more important than the latest “Tableau How To” video — is a workflow of how to ask better questions. There is such complexity in how government, government policy, health economics, and clinical medicine intersect I found that with my press credentials I had access to conversations not openly available to my colleagues.

A vital part of my understanding of the complexity of health law and policy is derived from The Week in Health Law — an important podcast always but perhaps even more so in the current era. A recent report Assessing Legal Responses to COVID-19 has been published by the George Consortium and is discussed and available for download. I attempted to discuss insights with a few colleagues but was disappointed that not many were even aware of its existence.

This collection of 36 expert assessments shows that the COVID-19 failure is, in important ways, also a legal failure:

Decades of pandemic preparation focused too much on plans and laws on paper, and ignored the devastating effects of budget cuts and political interference on the operational readiness of our local, state and national health agencies

Legal responses have failed to prevent racial and economic disparities in the pandemic’s toll, and in some cases has aggravated them — COVID-19 has highlighted too many empty promises of equal justice under law

Ample legal authority has not been properly used in practice — we’ve had a massive failure of executive leadership and implementation at the top and in many states and cities. — Summary of Findings and Recommendations

I have challenged well-meaning data visualizations attempting to provide clarity and information by providing access to data and access to a smart software platform. My fear was and is that we are missing the contextual arguments that provide relevance and meaning to our analytics. I think this report is a good place to begin.

How reliable is the data? Why isn’t the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) an independent agency? You know, like the authors suggest, akin to the Federal Reserve? Politics shouldn’t influence data collection and statistical rigor during a pandemic — think back to AIDS research during the AIDs crisis and to current COVID-19 or research into firearm prevention and deaths…

As Patricia Williams points out in her powerful closing reflections on this Report, these disparities do not arise from bad individual choices or biological differences between races but the social factors that shape people’s lives every day “in the ghettoized geographies that have become such petri dishes of contagion.” These disparities are not inevitable. We as a society have created them. Centuries of oppression through policies, norms, and institutional practices shape individual experience and over time have created the inequitable society we inhabit.

This report contains over 220 pages arranged into 35 chapters across multiple domains relevant to the discussions around race and equity during the COVID crisis. My hope is that you will read every word but here is a quick synopsis of what I reviewed before listening to a panel discussion Coronavirus Conversations: Racial Bias in the Healthcare System & COVID Outcomes presented by Duke Science and Society.

One thing I note from my experience either participating in or observing these discussions is our keen focus on the symptoms of racial disparities in health instead of the structural elements that allow them to continue. Our nation rarely gives voice to our 400 year (and counting) origin story which I would argue may not just be part of the problem — but the whole problem.

The report dares to state unequivocally — here is the cause, the remedy, and implementation steps to address these gaps in equity painfully revealed during this latest pandemic.

Congress should also amend the Public Health Services Act to add transparency and accountability mechanisms that require the U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary and CDC Director to provide scientific support for guidance and orders responding to the pandemic. In the face of executive failure or deliberate suppression of information,

it is urgent for Congress to mandate and fund efforts to assure the collection and dissemination of accurate data. Disease surveillance reports should require enhanced demographic data collection that includes sexual orientation, gender identity, and disability status.

I have taught several data workshops to bring tools like ArcGIS, Tableau, and simple coding to journalists and professionals attempting to either gather or access timely datasets. But here is the problem. Much of what we would need to illuminate and share data insights — isn’t being collected. Or even if it is collected — in the absence of harmonization or consensus on variables — how clear are the insights we can gather?

In particular, because most states have constitutional limitations on deficit spending, only the federal government can supply the resources needed to ensure adequate testing and personal protective equipment (PPE), and research in and distribution of countermeasures. Likewise, only the federal government can soften the pandemic’s economic impact and prevent it from exacerbating pre-existing inequities. The federal government needs to take more steps in each of these areas.

A recent COVID-19 dataset had captured “recovered”. Already confused by muddy definitions of “confirmed” cases I explored how determination was made in marking cases as recovered. What I was able to gather was crudely, a patient confirmed with covid but also non-dead.

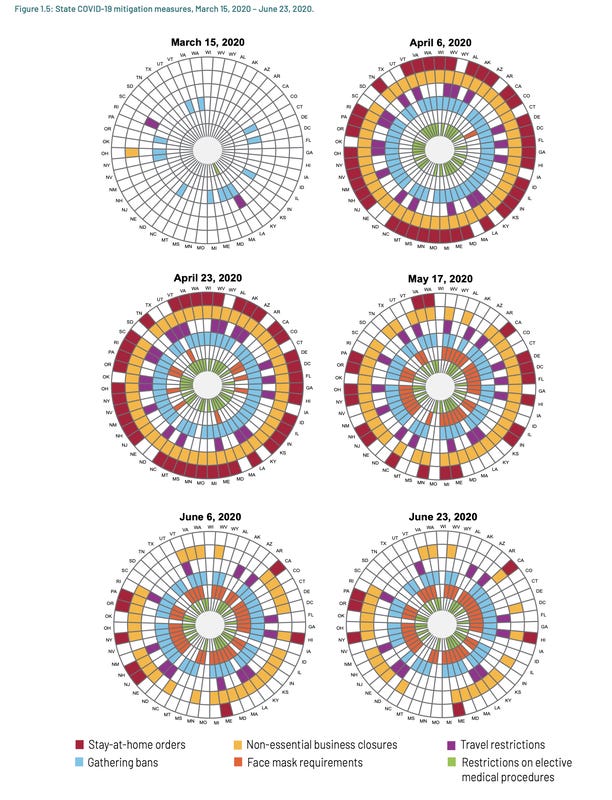

The graphic below is surprisingly useful at noticing adoption of mitigation measures in the absence of a national response. I will leave you to make your own conclusions.

“We can divide ourselves up into races and castes and neighborhoods and nations all we like, but to the virus-if not, alas, to us-we are one glorious, shimmering, and singular species. “ — Patricia Williams, JD

Pandemics, like climate disasters, thrive on inequality. COVID-19 is no exception, flourishing where inequality has weakened the social fabric. One of these weaknesses is long-standing racial discrimination, which has produced unjust, racialized disparities in COVID-19 transmission and mortality, and disproportionate economic harm to people of color. Efforts to address these racial disparities have been hindered by a series of governance and advocacy disconnects.

Some of these disconnects are well- known and widely discussed, such as fractures in federal, state, and local leadership that have politicized basic public health measures such as wearing masks. Less-well understood is the society-wide failure to adequately address racial discrimination in all its forms. This has perpetuated the disconnection of public health and civil rights advocacy from one another, and the disconnection of public health and civil rights professionals from anti-discrimination social movements. One promising tool to bridge these disconnects is research on the social determinants of health.

Highlighting the ways in which discrimination is a public health problem allows legal advocates to use civil rights law as a health intervention and public health advocates to squarely challenge discrimination. In keeping with the emergent health justice movement, civil rights and public health advocates can amplify their effectiveness by partnering with organizations that fight discrimination. We call this approach “ the civil rights of health .” This agenda for action requires (1) integrating civil rights and public health initiatives and (2) fostering three-way partnerships among civil rights, public health, and justice movement leaders (Harris & Pamukcu, 2019).

CHAPTER 35 * FOSTERING THE CIVIL RIGHTS OF HEALTH

Originally published at https://www.dataanddonuts.org.