Facts are stubborn things...

but statistics are pliable--Mark Twain

I am not an economist. My current super power is the ability to read. Read, hear, see, and think. I watch news when I can stomach it. It has long ceased to be that unassailable fourth estate of my youth but when you work in the business of words, you also can see past the hype directly into the eye of the beast.

The beast has a name and it is called inflation. The talking heads tell us inflation is bad and polling numbers point to who is to blame. We are an easy mark. Consider that we watched ginormous trailers parked outside of hospitals storing and hauling away dead bodies as they accumulated beyond capacity. And yet there are still millions of dumbasses refusing to get vaccinated or wear masks. Viruses mutate in the mucosa of unprotected hosts. Apparently so does stupidity. You do the math.

First, let’s talk about inflation. Go grab your beverage of choice. I’ll wait.

Inflation. What it is and how it is (or should be) measured. I have only one caveat. If I am wrong or horribly mistaken, let’s engage in a conversation to dispel my gap in knowledge. Yes, this will be perhaps painfully simplified but if the media is going to talk in soundbites and we are inclined to react—we should know more about what they are saying.

Inflation: the money in your pocket can’t buy as much as it used to…

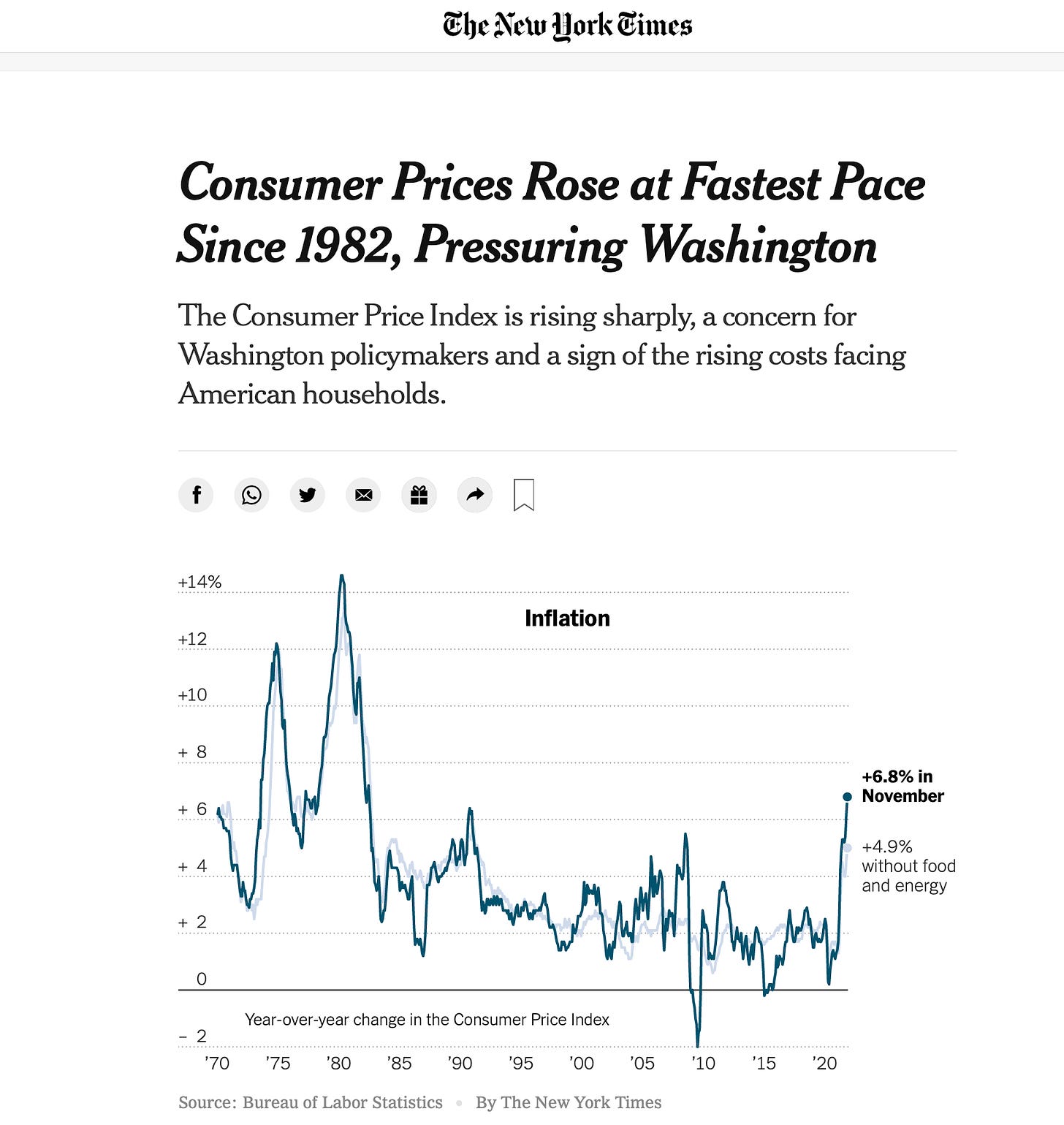

But let’s put a pin in that for a minute and remind ourselves of the reality of the past 2 years. We are still (whether we want to admit it or not) in the throes of a once-in-a-lifetime global pandemic. Whenever a talking head in the news media describes current inflationary rates in the absence of reminding the audience of this—they should be cancelled. Okay, maybe a little extreme but if the news is intended to inform—what the hell are they doing if they are just inciting the crowd?

Inflation is often the result of a strong economy—lots of dollars floating around and people are wanting to purchase. Think back to the often debunked but familiar universal applicability of the “supply and demand” curve. It is not the result of a single administration flipping a switch. Let’s see why or why not.

When demand is high, the price goes up in an effort to address a finite supply. Or companies facing scarcity of their goods figure why not jack up the price? Consumers will pay more because they know supply is limited. During the pandemic there were shuttered factories, supply chain interruptions, and giant shifts in the types of products in higher demand.

We have been made aware of supply chain woes limiting the supply of microchips, vehicles, and oil combined with the relentless purchasing power attributed to direct to consumer stimulus checks. This needs exploring but not sure those most impacted by lockdowns and company closures are clamoring for Peloton bicycles and new sofas.

Okay. But why are the TV graphics screaming about Consumer Prices or the Consumer Price Index (CPI)?

As far as I can tell, the CPI measures a range of spending behaviors—not inflation. To be clear it is known as an economic indicator. The producer price index (PPI) is another measure upstream from the CPI as it measures prices paid by say retailers or producers. We can make broad leaps and associate the index with inflationary rates but for the record—there are better metrics. These are important distinctions because this data is directly linked to public policy and how money is spent. The higher the CPI the more the government will need to allocate to payouts like social security, food stamps, military and federal retired workers, and school lunch programs. The CPI measures “all” urban consumers and urban wage earners and clerical workers.

The CPI reflects spending patterns for each of two population groups: all urban consumers and urban wage earners and clerical workers. The all urban consumer group represents about 93 percent of the total U.S. population. It is based on the expenditures of almost all residents of urban or metropolitan areas, including professionals, the self-employed, the unemployed, and retired people, as well as urban wage earners and clerical workers. Not included in the CPI are the spending patterns of people living in rural nonmetropolitan areas, those in farm households, people in the Armed Forces, and those in institutions, such as prisons and mental hospitals. Consumer inflation for all urban consumers is measured by two indexes, namely, the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) and the Chained Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (C-CPI-U).

The Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W) is based on the expenditures of households included in the CPI-U definition that also meet two additional requirements: more than one-half of the household's income must come from clerical or wage occupations, and at least one of the household's earners must have been employed for at least 37 weeks during the previous 12 months. The CPI-W population represents about 29 percent of the total U.S. population and is a subset of the CPI-U population.—US Bureau of Labor Statistics

The CPI measures the change in prices over a specific period of time for the purchase of a “market basket” of consumer goods and services. It is an important distinction that this basket is not current. There is a time-lag of several years. Detailed surveys collect data on the spending patterns of “professionals, self-employed, unemployed, retired people and urban wage earners and clerical workers”. For example, the 2020/2021 basket is based on 2017 and 2018 data.

You probably want to know what is in this “market basket”.

The CPI represents all goods and services purchased for consumption by the reference population (U or W). BLS has classified all expenditure items into more than 200 categories, arranged into eight major groups (food and beverages, housing, apparel, transportation, medical care, recreation, education and communication, and other goods and services). Included within these major groups are various government-charged user fees, such as water and sewerage charges, auto registration fees, and vehicle tolls.

In addition, the CPI includes taxes (such as sales and excise taxes) that are directly associated with the prices of specific goods and services. However, the CPI excludes taxes (such as income and Social Security taxes) not directly associated with the purchase of consumer goods and services. The CPI also does not include investment items, such as stocks, bonds, real estate, and life insurance because these items relate to savings, and not to day-to-day consumption expenses.

For each of the item categories, using scientific statistical procedures, the Bureau has chosen samples of several hundred specific items within selected business establishments frequented by consumers to represent the thousands of varieties available in the marketplace. For example, in a given supermarket, the Bureau may choose a plastic bag of golden delicious apples, U.S. extra fancy grade, weighing 4.4 pounds, to represent the apples category.

It isn’t a cut and dried calculation as these values are inconsistent. This little market basket we have been speaking of can be manipulated and you can imagine that it might be advantageous to have this methodology shift—impossible to know since there is little transparency of the “raw” data.

“If the selected item is no longer available, or if there have been changes in the quality or quantity (for example, eggs sold in packages of ten when they previously were sold by the dozen) of the good or service since the last time prices were collected, the economic assistant selects a new item or records the quality change in the current item.”

…In other words, the CPI doesn’t measure changes in consumer prices, rather it measures the cost-of-living. Further, the government makes the assumption that consumer spending habits change as economic conditions change, including rising prices. So if prices rise and consumers substitute products, the CPI formula could hold a bias that doesn’t report rising prices. Not a very accurate way to measure inflation.—Forbes

So the part of all of this that remains squishy for me—we do not count about 25 million people in the population—what they are doing isn’t relevant for the statistics even though headlines report the impact of the pandemic on rural populations (not included in CPI) and let’s not forget the 800,000+ members of the US population that have died from Covid. The elderly were disproportionately impacted by the first waves of Covid — how does this impact indices and are adjustments needed?

As members of the American populous we also need to understand policy. How do big signature pieces of legislation impact the conversation? When there is clamoring across media and it seems to the populous that these are different issues—I assure you, there are connections.

Here is a tutorial for those curious about how investments in infrastructure impact the economy—Effect of Physical Infrastructure Spending on the Economy and the Budget Under Two Illustrative Scenarios.

Infrastructure spending serves a number of goals besides economic productivity, and those social goals may lower the effect of that spending on economic output. For instance, spending for water utilities may emphasize providing cleaner water; spending for transportation infrastructure may focus on expanding access, improving safety, or reducing the environmental impact of travel; and subsidies for broadband communication may boost living standards. Those benefits to society do not necessarily translate into increases in GDP.

Social goals may also be addressed by the way in which infrastructure is built. The Davis-Bacon Act requires workers on federally funded construction projects to be paid the prevailing local wage. CBO estimates that repeal of the act could reduce federal outlays by $1 billion a year over the next 10 years as a result of paying workers lower wages. Two Buy America provisions require that state and local governments use iron and steel made in the United States and that other manufactured goods used in federally funded transportation projects be produced and assembled domestically. Those provisions increase the costs of infrastructure in order to support American production but do not generally boost the productivity gains stemming from completed projects. CBO has not analyzed the quantitative effects of those provisions on the economy.—Congressional Budget Office

These are important resources to understand because the news doesn’t hold space for the entire story or context. We are often left with binary incendiary claims keeping both sides woefully uninformed. For or against, good or bad, patriot or socialist.

Why the gnashing of the teeth over inflation? Think fixed-income assets. Many differ in the maturity (T-bills, T-notes, T-bonds), protection from inflation (treasury inflation-protected securities or TIPS) and who is backing or issuing the bond (municipality or county for example). The purchasing power of a Treasury bond’s value is linked to interest rates. Treasury bonds are loans to the federal government. They are low risk, low yield but safe investments. Remember that high inflation rates can cut into interest you earn on your investments. The news is also reporting record low unemployment. Employers are now paying higher wages and will pass these additional costs to the consumer. The consumer will be paying more for goods and services. Sound familiar?

We downplay the credit risk as it is unlikely the government will default in these investments. There are fixed-rate bonds and bonds that are pegged to inflation rates. Obviously more risk, more potential benefit. The interest rate risk is the main concern when dealing with government backed and issued bonds for example. In very general terms, the sale of these bonds are a source of income for the federal government (along with taxes) and the 10-year bond serves as a benchmark for longer-term interest rates. If interest rates fluctuate your bond is now competing with newer bonds coming onto the market with higher interest rates. A buyer is not going to want to purchase at a loss so now you are stuck waiting to your bond matures (10 years). This is simplified but explains why the combination of inflationary rates and forward thinking of future interest rates impacts bonds, mortgages, vehicle and personal loans, savings rates, student loans and on and on.

I invite you to be curious. Clearly not all categories in the CPI impact the index the same. But you would be hard-pressed for media that states or clarifies the details. Below is the 12-month percentage change in the CPI in selected categories. There is similar granularity when we look at unemployment data (not all industries are doing well) or other economic indicators.

Don’t always believe the summary statistics.

“Facts are stubborn things, but statistics are pliable”— Mark Twain