And however undramatic the pursuit of peace, the pursuit must go on...

John F Kennedy addressing the United Nations

Each chapter of 1963| autobiographicacy; a year in statistical thinking is themed by specific events worthy of a deeper dive. I have been drafting a few sample chapters and decided to include them here. Here is one of the highlights from the chapter on May 1963.

Civil-rights sit-in case decisions

I am not a legal scholar but it is imperative to discuss the rulings in 1963 by including the cultural climate and historical upstream precedents.

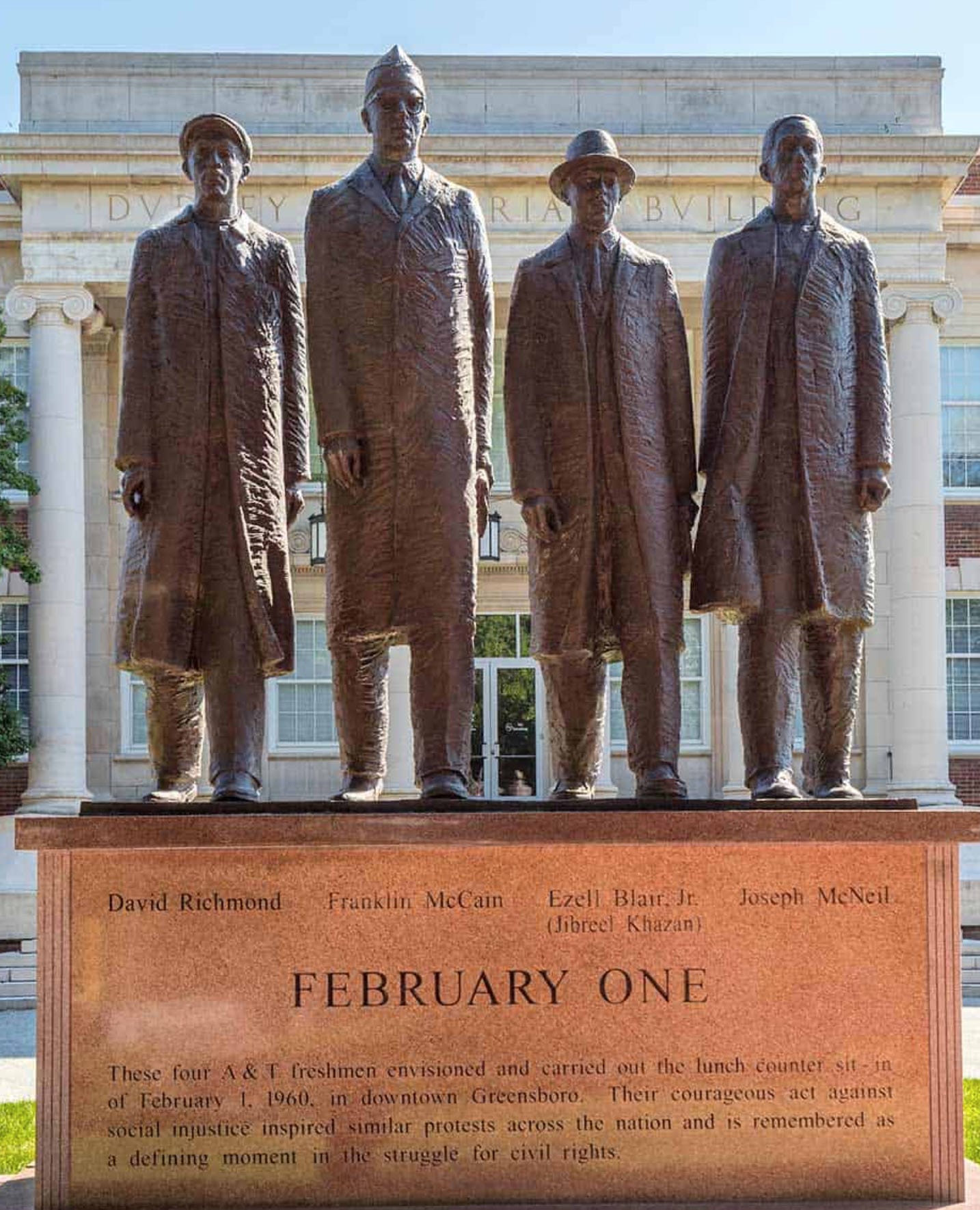

I live within walking distance of the Woolworth’s lunch counter sit-in that began February 1, 1960. As a young student I visited Washington DC and the Smithsonian Institution that houses a portion of the counter for public display. It never occurred to me the whereabouts of the remaining counter and I don’t remember if we were told about Greensboro specifically or simply about sit-ins in general.

If you are like me and thought there was perhaps a single driving force that desegregated lunch counters—I mean, weren’t we post fourteenth amendment, Jim Crow, and Brown vs. Board of Education—who could blame you? The truth exists somewhere between formal legal change leading to social change (and vice versa) and examining how law functions within different institutional and social settings.

The constitution never fully empowered The 14th Amendment to specifically address discrimination of private enterprise but instead relied on a weird tea brewed from the Commerce Clause, Brown v Board of Education and deciphering what is and isn’t a state right in regard to private enterprise. The final rulings of the Supreme Court reversed a host of earlier lower court decisions on a single day in May 1963.

Historically it would seem appropriate to hold the sit-in convictions as a violation of the equal protection clause (part of the Fourteenth Amendment) which took effect in 1868. Drafters of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 actually relied on Congress’ Commerce Power falling short of liberating Congress’ authority to enforce provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment—a strong statement that would have summarily established sit-in prosecutions as a violation of rights under the Constitution.

Following are reminders of these important pieces of legislation.

Section One of the Fourteenth Amendment

“No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

ArtI.S8.C3.1.2 Commerce Among the Several States

[The Congress shall have Power . . . ] To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes; . . .;

The Commerce Clause serves a two-fold purpose: it is the direct source of the most important powers that the Federal Government exercises in peacetime, and, except for the due process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment, it is the most important limitation imposed by the Constitution on the exercise of state power.—Constitution Annotated

In 1954, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was decided unanimously in favor of Brown stating “separate educational facilitates are inherently unequal” violating the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution.

By 1960, the Court, through a series of per curiam (unanimous decisions) had expanded beyond the decision of Brown ending school segregation to prohibiting segregation at the state level although leaving the equality mandate to struggle when applied to privately- owned facilities opened to the general public.

Although we think of Monday, February 1, 1960, and the infamous lunch counter of a Woolworth store as the genesis of the sit-in movement it actually wasn’t the first sit-in. The historical significance of this date commemorates the protests spreading beyond local geography. These weren’t simply local events anymore but were beginning to spread across the country.

Risa Goluboff, an editor at the Harvard Law Review, Lawyers, Law, and the New Civil Rights History, mentions the vertical nature of civil rights history. It measures a flow “of consciousness, arguments, and doctrine throughout the process” of how laws are imagined and subsequently created.

Here are the 1963 decisions supporting the protestors and the violation of their civil rights.

Peterson v. City of Greenville May 20, 1963

As a review of the lower court decision in South Carolina, the supreme court had a majority vote with Harlan as special concurrence. A special concurrence means that although Judge Harlan agreed with the majority decision he did not agree with the reasoning behind Chief Justice Warren’s majority opinion.

Petitioners, ten Negroes, entered a store in Greenville, S.C., and seated themselves at the lunch counter. The manager of the store did not request their arrest, but he sent for police, in whose presence he stated that the lunch counter was closed and requested everyone to leave the area. When petitioners failed to do so, they were arrested, and later they were tried and convicted of violating a state trespass statute. The store manager testified that he had asked them to leave because to have served them would have been "contrary to local customs" of segregated service at lunch counters and would have violated a city ordinance requiring separation of the races in restaurants.

Held: Petitioners' convictions for failure to leave the lunch counter violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, even if the manager would have acted as he did independently of the existence of the ordinance. Pp. 373 U. S. 245-248.

Avent v. North Carolina: May 1963

The Court vacated the North Carolina Supreme Court’s judgment and remanded the case for reconsideration based on decisions in Peterson v. City of Greenville (states cannot use trespass laws to enforce discrimination mandated by a segregation ordinance).

“For the convictions had the effect, which the State cannot deny, of enforcing the ordinance passed by the City of Greenville, the agency of the State. When a state agency passes a law compelling persons to discriminate against other persons because of race, and the State's criminal processes are employed in a way which enforces the discrimination mandated by that law, such a palpable violation of the Fourteenth Amendment cannot be saved by attempting to separate the mental urges of the discriminators.”—Chief Justice Harlan

Justice John Harlan dissented in part. “My differences with the Court relate primarily to its treatment of the state action issue and to the broad strides with which it has proceeded in setting aside the convictions in all of these cases. In my opinion the cases call for discrete treatment and results.” He pointed out that the City of Durham had a restaurant segregation ordinance in effect, but that the North Carolina Supreme Court proceeded under the assumption that no such ordinance existed. He found the cases to have unique merits of their own and objected to addressing them collectively.

Five black students and two white students were convicted of criminal trespass after sitting at a lunch counter in Durham, N.C., a city which had an ordinance requiring racial segregation in public eating places. In a per curiam opinion, the Court reversed the convictions citing Peterson v. City of Greenville.

Gober v. City of Birmingham: May 20, 1963

Ten black students were convicted of criminal trespass in Birmingham, Ala., for sitting at white lunch counters and failing to leave when asked. In a per curiam opinion citing Peterson v. City of Greenville, decided the same day, the Court reversed the convictions. Again, there is no ruling based on civil liberties—only interpretation of already existing laws.

Again Harlan dissents, “My differences with the Court relate primarily to its treatment of the state action issue and to the broad strides with which it has proceeded in setting aside the convictions in all of these cases. In my opinion the cases call for discrete treatment and results.”

Lombard v. Louisiana May 20, 1963

This case involved three black students and one white student who sought to be served at a lunch counter in New Orleans, contrary to prior announcements by the mayor and superintendent of police that “‘sit-in demonstrations’ would not be permitted.”63 The Court treated these “officials’ statements … exactly as if [New Orleans] had an ordinance prohibiting” desegregated service in restaurants,64 and reversed the convictions. In the absence of state statute or city ordinance requiring racial segregation in restaurants, the Mayor and the Superintendent of Police had publicly announced that "sit-in demonstrations" would not be permitted.

Held: Petitioners' convictions violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Peterson v. City of Greenville, ante, p. 373 U. S. 244. Pp. 373 U. S. 268-274.Justice Douglas concurred, noting privately owned enterprises open to the public are subject to regulation and may not discriminate.

I refer you to scholars for the in-depth discussion of how the needle on social change moves and the extent of impact by policies and legislation. My point in highlighting this time in May 1963 is to perhaps share the highlights out of the grasp of recollection. The clause that left the 14th amendment open to interpretation involves states rights.

In fact, this has been referred to as the Great Aberration of the Warren Court. Although advancements were made under the leadership of Chief Justice Earl Warren (1953-1969) in the representation of school desegregation, criminal justice and voting rights—the rulings regarding sit-in demonstrations at lunch counters were narrow victories. This yielded support for the student protestors but avoided a constitutional reform in response.

May 1963 Table of Contents:

Civil rights sit-in case decisions (here)

Mercury Atlas 9 completed 22 earth orbits,

Dutch New Guinea given to Indonesia,

Bluebird-Proteus disappointment,

Police dog attacks 17 year old protestor in Alabama,